|

|||

|

|||

Musique Concrète

Musique Concrète was the first of three main types of electronic

music, being followed by synthesizer works, and computer composition.

The development of microphones, variable speed tape machines, and sound

editing techniques resulted in the creation of the first electronic music studio

in 1948.[i]

The studio was established in Paris by French radio broadcaster, Pierre

Schaeffer. Musique Concrète

used sounds from nature (rather than electronically produced sounds) that could

be distorted and manipulated in order to create musical works.

Composers of Musique Concrète made use of many features of tape,

looping sounds, playing backwards, varying speeds and often splicing sounds

together. Techniques were generally

time consuming and it could take several months to make a piece only a few

minutes in length. One of the most

well known techniques used to manipulate and combine the sounds was splicing,

this involved cutting and rejoining a piece of tape, either to another piece of

tape or to itself in order to create a loop.[ii]

However, with experimentation composers developed many different ways of

doing this using diagonal and even horizontal cuts so that material could be

spliced together at a variety of angles. In

addition, pitch was changed by varying playback speeds, and lightly touching the

tape in playback could produce a flanging effect.

Because of Musique Concrète technology specifically for them was

developed, such as the Phonogene and the Morophone.

The first of these was created by Schaeffer and designed to transpose

loops by using a set of varied diameter capstans that could be selected using a

keyboard.

The idea of Musique Concrète is in many ways

similar to the Futurist audible ‘landscapes’ written for radio in 1933 by

Marinetti, below is a description of one such work, Silences Speaker to each

other :

15 seconds pure silence, do, re, me on the flute, 8 seconds

of pure silence, do, re, me on the flute, 29 seconds of pure silence, sol on the

piano, 40 seconds of pure silence, do on the trumpet, the cry of a baby boy, 11

seconds of pure silence, 1 minute of the “rrrrrr” of a motor, 11 seconds of

pure silence, the surprised “ooooooo!” of an 11 year old girl.

Although many of the sounds used in these pieces were naturally produced, mechanical sounds were also included, such as the noise of a motor. It is interesting that these works were designed specifically for radio, so that while still being performances, they were only audible performances. This shows the interest that developed among some composers for using technology such as radio and the loudspeaker to create audible environments.

The Futurist movement was very interested in breaking

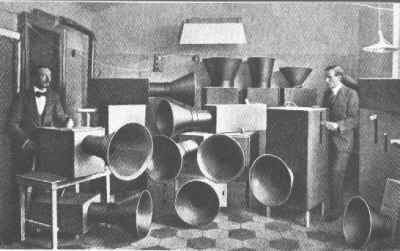

free from convention, and music was not excluded. In 1914, Luigi Russolo made several performances using

instruments or rather noise machines that he had created with Balilla Pratella.

These instruments known as intonumori or Bruituers, producing grumbling

and hissing noises after which they were named, and were mainly combined with

more traditional instruments.

Futurist music was followed by Milhaud’s experiments

with varying record speeds, and in the 1930’s works such as Imaginary

Landscapes by John Cage (1939 – 42) were produced.

Some composers attempting to introduce technology from the outside world

into their works, e.g. incorporating

airplane propellers into ballet music[iii].

The main technological advance that led to Musique Concrète was

the tape recorder, allowing composers to manipulate recorded sound much more

than they had be able to before.

Several works soon followed after the creation of Schaeffer’s electronic studio, including Etude aux casseroles, and in 1951 a group headed by Schaeffer, le Groupe de Recherches Musicales, was formed to research the new form. As time passed works became more complex, composers varied elements such as rhythm more than before. Musique Concrète was not just about recorded works as some composers worked live. Compared to recorded works, live works used less of the techniques associated with this form, as they were simply not practical for live work. Instead, live works often used collections of microphones, positioned in the performance environment, that would collect sounds and feed them through variable speed phonographs, and be altered using filters. People continued to produce both live and recorded works and in 1965 John Cage produced the live work Variations IV. This made use of microphones and phonographs to collect and process environmental sounds, and add pre-recorded sounds resulting in a complete composition. Soon, works started to be incorporated into film and visual art performances, and composers started to combine other technologies in their works. For example Varese’s use of film projectors and lamps to create special visual effect for his work Poem Electronique. John Cage had used electronic sounds in his works for quite some time, Imaginary Landscape no. 3, written in 1942 used variable speed phonographs, audio-frequency oscillators, an amplified wire coil, an electric buzzer and an amplified marimba. Cages interest in using modern technology in his works continued and Imaginary Landscape no. 4 used 12 radios, operated by performers who, following notated instruction, manipulated volume and tuning of the radios. The performances were thus, in part, determined by the material being aired at the time. The fifth Imaginary Landscape work written in 1952 was the first of Cage’s tape works, combining a mixture of sounds from gramophone records.